The colour of safety

Spall 006: Form, function, and #f5a500

October 3, 1927. In the soft light of early dawn, a boy stands at the edge of a dirt road somewhere outside Des Moines, Iowa. He wears wool knickers and a jacket two sizes too large, the kind that's passed down until it disintegrates. Surrounded by yellowing fields, he waits for a vehicle to emerge from the corridors of drying corn. Sometimes it’s a neighbour’s tractor pulling a makeshift wooden wagon, sometimes a repurposed Model T with benches crudely bolted inside. On rainy days, the pickup might fall through. If he’s lucky, someone will arrive. If he’s not, he walks.

On the other side of the country, the scene isn’t much more organized. In a growing suburb outside Boston, a half-dozen children clamber into the back of a retired delivery van owned by a local grocer. There are no seats, only crates and flour sacks. There's no schedule either. Pickup times depend on weather, traffic, or whether the driver stops at the market first. The children don’t complain. It’s still better than walking along the trolley tracks.

This was school transportation in North America before regulation. Not really a system so much as a patchwork of chance and improvisation. Horses gave way to homemade contraptions, canvas roofs stretched over welded frames, each route as unique as the child riding it. Safety was contingent on weather, the alertness of passing drivers, and, in many case, just having good fortune.

And while you'd see the occasional yellow vehicle, it was just one of many pigments painted onto buses, wagons, and family cars repurposed for school duty. There were no federally mandated stop arms, and no expectation that traffic would halt for a child on the roadside. The trip to and from school was a daily improvisation of getting bodies from scattered farms and neighbourhoods to the institutional centre.

By October 1940, that impromptu routine would harden into infrastructure, be painted a particular hue, codified in law, and built to last.

Yellow was once a verb. Not to yellow, in the sense of age or decay, but something closer to the concept of a flicker. Its linguistic ancestors—gelwaz in Proto-Germanic, ghel in Proto-Indo-European—meant not just the colour itself, but the sense of shining, gleaming, of being golden. To be yellow was to catch the light.

As is so often the case when you probe linguistic roots, ghel forms a strange constellation. There's gold and glitter, but also glare and gall. Brightness but also bile. Across ancient languages, yellow was the colour of what glowed and what warned, what shone and what sickened. It’s this doubleness, the ability to oscillate between welcome and warning, that gives yellow its enduring cultural voltage.

You can even see it play out in nature. Yellow rarely whispers. Among insects, reptiles, and amphibians, it’s a high-frequency signal used not for camouflage but confrontation. The yellow of a wasp, the dart frog, the fire salamander, all announce the same message: stay away. Evolutionary biologists call this aposematism, a visual warning system honed over millions of years to deter predators. Paired with black, yellow becomes part of a primal visual code. Danger resides here.

And yet, in the plant world, yellow often connotes the opposite. Sunflowers, goldenrod, canola, these are not warnings but invitations. They seduce pollinators, coaxing bees and butterflies toward their nectar. Yellow is lure, not alarm. The warm, open mouth of life in bloom.

It’s this instability that made yellow a perfect tool for modern industry. Unlike blue, which recedes, or green, which blends, yellow projects. It demands to be seen. That’s why hazard signs, wet floor placards, and roadway markings all gravitated toward it. Not out of aesthetic preference, but optical necessity. Yellow is among the most visible colours to the human eye, especially in low light. It exists in that liminal zone where visibility becomes imperative, where missing a detail might mean harm.

But it wasn’t until the 20th century that yellow began its transition from symbolic to systemic. In 1915, an American entrepreneur named John Hertz ordered his taxi fleet painted yellow. You'd think that this was a brilliant bit of branding—and in a roundabout way it was—but the real reason for the choice was more basic. A study at the University of Chicago had found yellow was the most visible colour at a distance, so it was the perfect hue to drape across a fleet of cabs.

That one decision created an urban archetype, and offered an important precursor to later developments around school transportation. So, by the time someone got around to institutionalizing the educational commute, the choice was never arbitrary. It was evolutionary, urban, and industrial. But it took some time for it to stick.

Even before regulation, the instinct for visibility had begun to take hold. Across rural North America, school transport was a patchwork of "kid hacks," retrofit vehicles that shuttled children to class on wooden benches nailed into wagons or truck beds. Most were unpainted or blended into the agricultural palette: barn red, weathered wood, or the dust of the road itself. But here and there, a change was creeping in. Yellow, unstandardized and varying by region, was beginning to appear. It wasn't a mandate, but you could say it was the function of intuition.

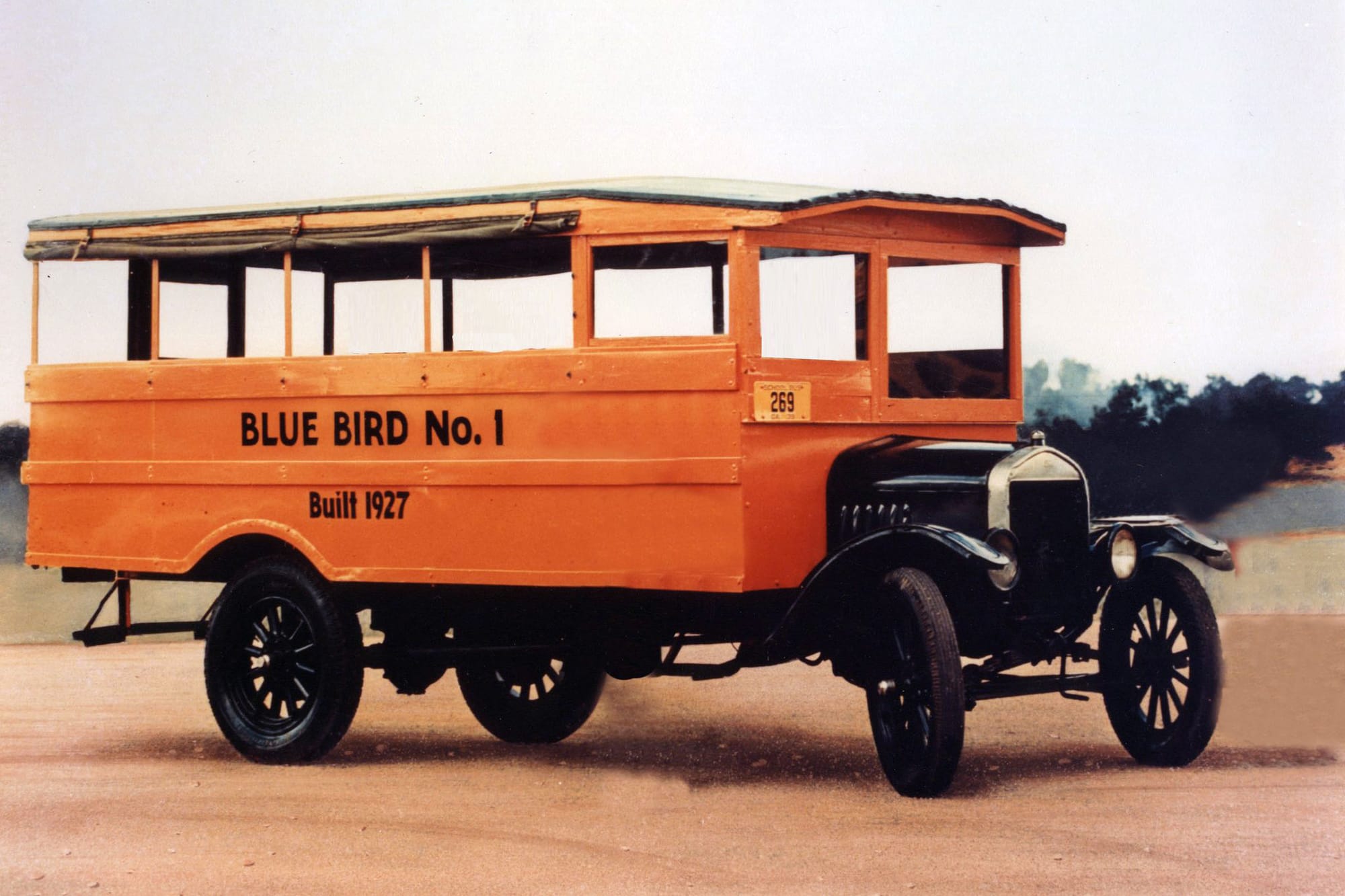

In 1927, a Georgia car salesmen named Albert Luce introduced what many now recognize as the first modern school bus. Built with a steel body on a Ford chassis, his Blue Bird No. 1 was painted a bright, unmistakable yellow. Not orange, not gold, but something calibrated to be seen, be it at dawn, in fog, or on winding roads. Luce had no federal guideline to follow. What he had was a sense of what worked. His bus was sturdy, symmetrical, and clearly made for its purpose. In form and in pigment, it marked a turning point.

Twelve years later, that intuition became law. In 1939, educator Frank Cyr convened a national conference at Teachers College, Columbia University. Representatives from all 48 states gathered to bring consistency to the chaos. Over seven days, they drafted 44 standards for school transportation, ranging from aisle widths, body dimensions, emergency exits, and, most iconically, a single colour. It would be known as National School Bus Glossy Yellow, chosen for its contrast with black lettering and its legibility in low light.

Since these regulations came into place, the colour has mostly held, even if it lacked an official hex code. We now use #f5a200, but it's descriptive rather than prescriptive. In practice manufacturers interpreted the hue slightly differently, often depending on paint suppliers, regional materials, and weathering treatments. In photos from across the continent, you'll detect some variation, but as a complete package, the school bus always seems like it's that yellow.

And that's because this wasn’t about pigment so much as the visual codification of order. A yellow bus in Alabama means the same thing as one in Vermont, and in Saskatchewan, too. It signals caution to drivers, coordination to parents, and control to administrators. The bus became a semiotic system. Form, function, and fear, all fused into one moving object.

While the yellow we've come to so well was the shiny highlight of that 1939 conference, it was but one of many regulations that transformed school transportation from an ad hoc necessity into a formal apparatus. A system that manufactured order and extended the reach of the school as institution far wider than just classrooms and playgrounds.

From aisle widths to emergency exits to the federally recognized hue of a moving vehicle, every element became legible, interoperable, and enforceable across the continent. The stop arm that swings out when children disembark? Standardized. The sequence of flashing amber and red lights? Regulated to cue driver behaviour from blocks away. Even the tall, padded seat backs, which are designed to compartmentalize children in case of collision, are federally mandated.

On the surface, it was about safety. But safety was the gateway to something deeper: regulation, rhythm, and control. Infrastructure, of course, is neither neutral nor accidental. The school bus served to protect children but also to position them. It embedded them within a temporal machine as much as a spatial one. The morning pickup, the afternoon drop-off, the expectation that a child would arrive on time, enter the institution, and be accounted for—all of this underwritten by the yellow symbol at the heart of the system.

Here is Michel Foucault's notion of discipline in its softest form. Not punishment, but structure. Not coercion, but choreography. The bus became the mobile front line of the educational order. Children stepped into its frame before they reached the school, subject to the same rules, the same timing, the same hierarchy of movement and stillness. The yellow bus was less a vehicle than an instrument of governance disguised as a ride.

And the colour was as formative as it was functional. It taught drivers to stop. It taught children to wait. It taught everyone to recognize the presence of the state in everyday life. Its pigment conditioned behaviour just as intended, soft control meant not for malice so much as paternalism.

Once the system was in place, it began to spread, not just geographically, but conceptually. Yellow, now codified as the colour of scholastic safety, started to radiate outward. School zones were marked with yellow pavement. Crossing guards wore yellow vests. Signs adorned with imperatives like "Slow Down!" were cast in yellow near playgrounds and parks. The child’s journey became not just protected but bracketed, inscribed by a colour that signalled caution, control, and compliance.

But, crucially, yellow’s work didn’t stop at visibility. It became part of the architecture of time. The school bell, the timetables, the choreography of hallway movements, all these are part of what Foucault would call the disciplinary diagram. The bus was only the beginning. It extended the institution’s reach into the landscape, but the real power was in its coordination of bodies. What time you woke, what route you took, how long you waited. We tend to call these habits, but they are, in fact, orchestrated, rehearsed, and enforced. Yellow, once the colour of light and bile, became the colour of order.

Because order is safety.

October 3, 2039. At the edge of a cul-de-sac in a planned community outside Tempe, Arizona, a child waits. She's eight years old, wearing a backpack with reflective strips and a school ID clipped to the front. What arrives isn’t quite a bus in the old sense, more like a low-slung, electric shuttle. There’s no driver. No steering wheel. Just a LiDAR dome on the roof and a row of discreet cameras along the frame.

She scans her ID at the door, waits for the green light, and climbs aboard. A remote monitor in a central control room notes her entry. Inside, the seats are composite plastic and the air faintly antiseptic. Her name appears on the panel above seat 6C. She buckles in. The bus pulls away soundlessly, threading its way through a geo-fenced suburban route built specifically for this pilot project.

What colour is the bus? The same it’s always been.

We don't know exactly what school transportation will look like in the next couple of decades, but there's every reason to believe that a century after federal regulation and a bewildering amount of technological progress, the ceremony of pickup and drop-off will persist with sacred consistency. In an era obsessed with disruption, the yellow school bus endures. Not because it resists change per se, but because it encodes the stability of the system.

Even today, its reach expands. Electric school buses now roll off assembly lines in Quebec and California, their motors silent, their interiors high-tech, but their exteriors still burn the same brilliant yellow. Autonomous prototypes are tested in controlled districts, with AI-driven sensors scanning intersections for motion, yet their bodies still wear the chromatic code of 1939. The pigment survives because the structure does.

In this way, yellow becomes more than a colour. It’s a carrier of memory, of rhythm, of governance by design. For all its youthful associations, it's not a symbol of nostalgia, but a signal of what still works. And here’s where we begin to see its real genius. The system doesn’t feel like a system at all. The bus just “is.” The child waits because that’s what one does.

It’s only when you look again, when you peel back the skin of the everyday, that the scaffolding becomes visible. A single colour, chosen for its optical intensity, becomes a substrate of civic life. One that teaches us how to behave before we even realize we’ve learned anything.