The colour of safety

Spall 006: Form, function, and #f5a500

October 3, 1927. In the soft light of early dawn, a boy stands at the edge of a dirt road somewhere outside Des Moines, Iowa. He wears wool knickers and a jacket two sizes too large, the kind that's passed down until it disintegrates. Surrounded by yellowing fields, he waits for a vehicle to emerge from the corridors of drying corn.

The shape of dread

Spall 005: From the tetrapod to the lattice

The world is made of shapes. Most serve without asking for attention. They fit our hands, our bodies, our sense of what belongs. Some are tools of comfort, some of harm, but all speak, in their way, our language of form.

And then there are the shapes that don’t. Some feel wrong the moment we

The architecture of anxiety

Spall 004: Blasts, bunkers, and evacuation plans

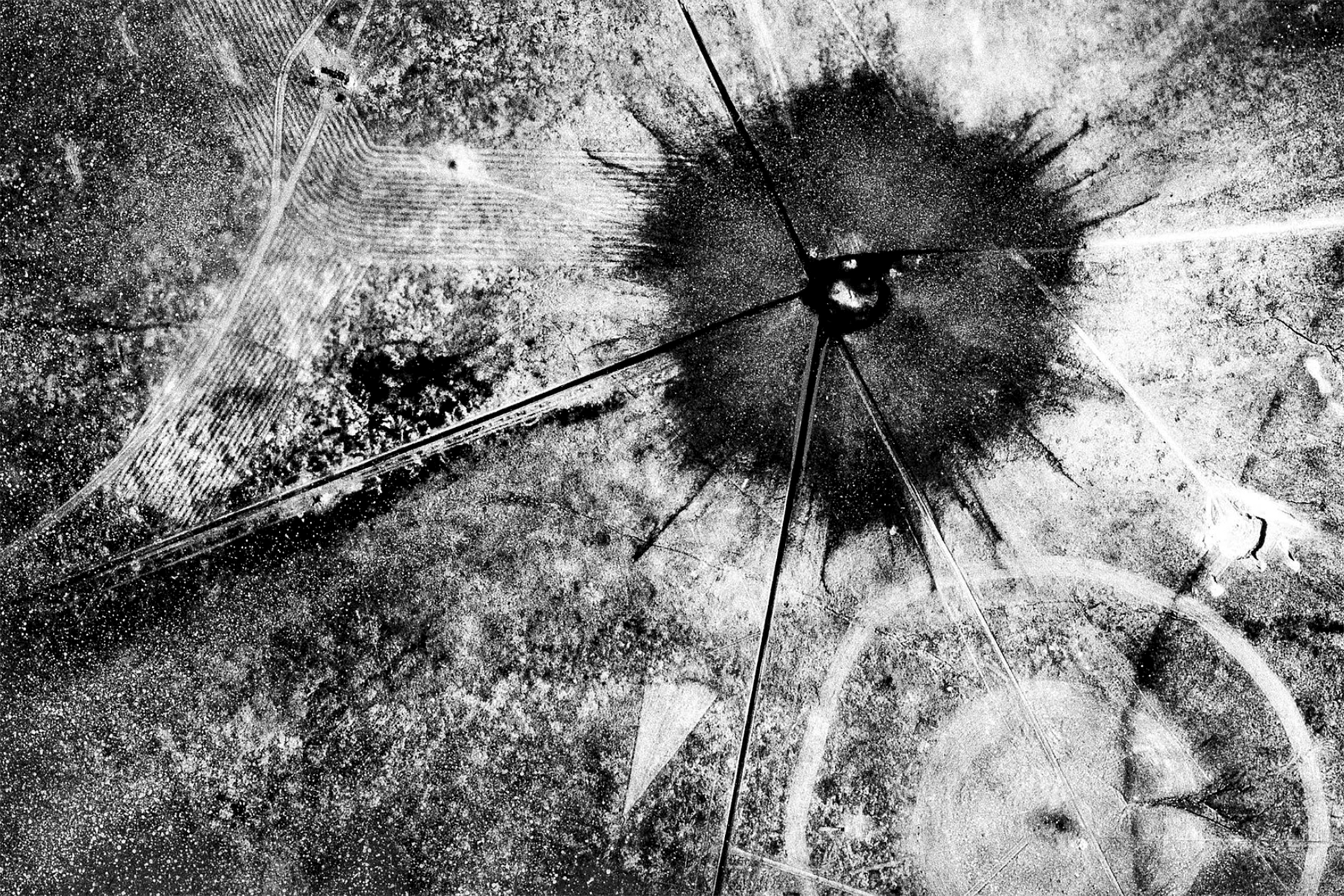

Seen from above, the site of a nuclear detonation does not look like a wound so much as a signature, a blackened bloom branching out in delicate, finger-like striations across the landscape. As though something enormous had signed its name in the flesh of the earth. A diagram of violence laid bare: the circular

Fata Morgana and the sky that folds

Spall 003: Mirages, UAP, and the architecture of illusion

It happens in spring.

The lake contracts, reshapes itself. Shoreline sixty kilometres distant, hidden below any natural eyeline, rises up to flank the horizon. Looking south from Toronto, the distortion poses first as clarity—as if the day were simply sharp enough to reveal the edge of upstate

The temperature of night

Spall 002: Light, memory, and the infrastructure of feeling

I grew up in a duplex apartment. While short of a bird’s-eye view, the living room window offered just enough elevation that the nearest streetlamp stood nearly level. As such, it occupies an outsized presence in my earliest memories. Fashioned in the “acorn” style common across Toronto from the post-war period through the 1990s, its incandescent

First, there were fractures

Spall 001: A brief genealogy of extraction and accumulation

In the mining regions of 17th-century Saxony, where timbered adits webbed the hillsides and extraction was measured by mule-load, a new entry begins to appear in the margins of guild records and yield ledgers: “spall.” It was not a commodity