The architecture of anxiety

Spall 004: Blasts, bunkers, and evacuation plans

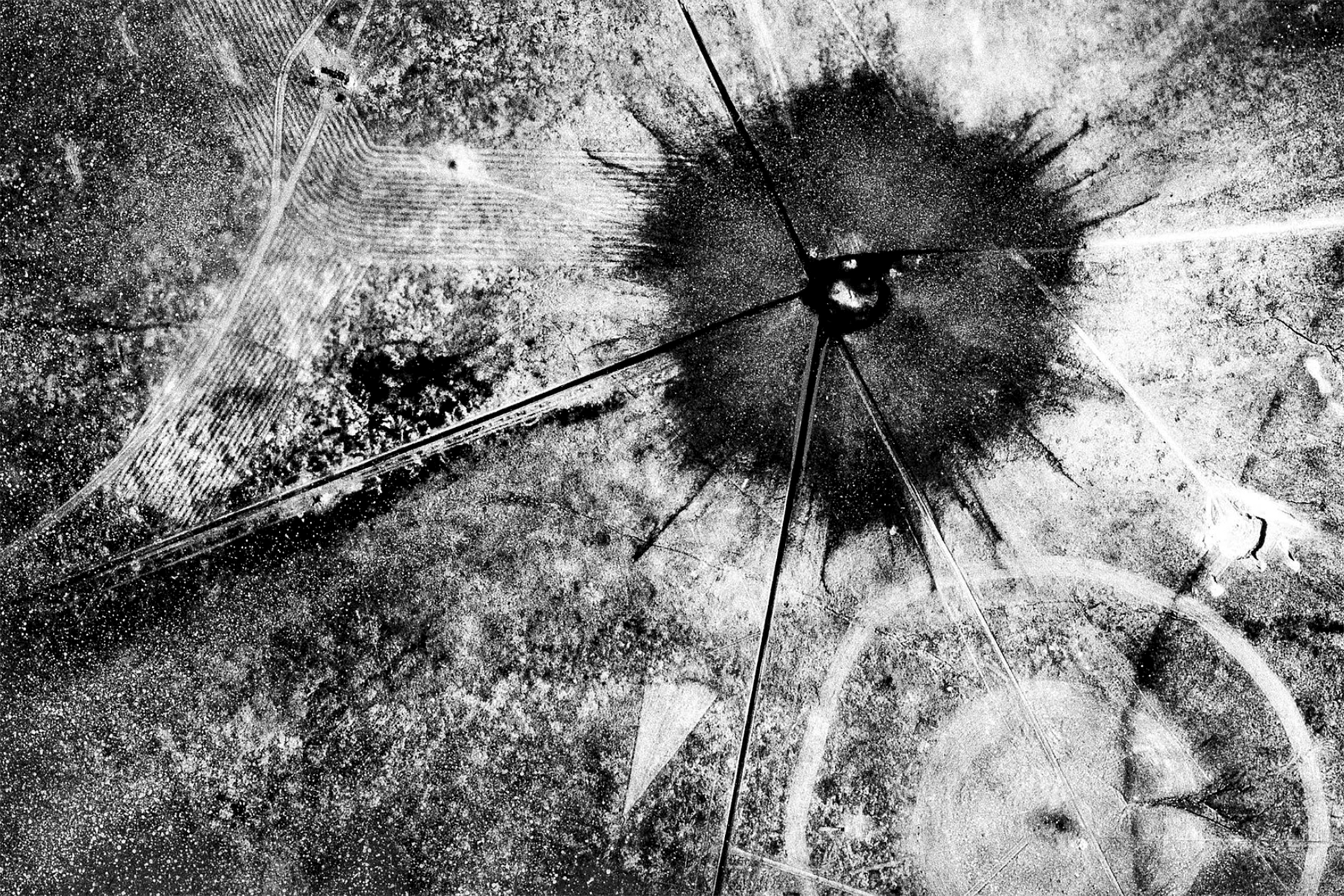

Seen from above, the site of a nuclear detonation does not look like a wound so much as a signature, a blackened bloom branching out in delicate, finger-like striations across the landscape. As though something enormous had signed its name in the flesh of the earth. A diagram of violence laid bare: the circular blast zone, the radial fractures, the scorched and ghosted peripheries—all of it captured in a single instant of rupture.

This is spall at its most elemental. Not the slow exfoliation of rock or the crumble of concrete under strain, but the immediate unmaking of matter. A pressure system pushed beyond its limits, geological or geopolitical, until something gives. What once seemed solid reveals itself as porous, contingent, breakable.

During the Cold War, planners and engineers worked feverishly to model these ruptures. They calculated blast radii, mapped evacuation routes, drew concentric rings of devastation across city centres. But even in the most clinical renderings, something uncanny remained: a lingering sense that no diagram, no contingency, could fully account for the event itself.

In 1979, a satellite orbiting the South Atlantic recorded an unusual event. A flash, then darkness, then a second, longer flare. Scientists recognized the pattern immediately: the “double flash,” an unmistakable signature of a nuclear detonation. And yet, no nation claimed responsibility. No confirmation ever came. In that sliver of darkness between bursts, the world had changed—but the event went officially unacknowledged. First rupture, then revelation. And then silence.

I grew up in the 1980s. The colours were bright, the malls full, and the cartoons loud. Beneath it all, I was terrified.

By the time Top Gun came out, I carried a persistent, unspoken nuclear anxiety. I’d wake in cold sweats from dreams that began with a siren and ended in a flash. If there was unrest in the Middle East—or even a mention of escalation—I braced for World War III. My friends never talked about it. My parents never seemed worried. But I still felt it in my chest: the quiet certainty that something irreversible could happen at any moment.

Years later, reading Douglas Coupland’s Generation X, I recognized something I hadn’t known could be named. The novel follows three people in suspended adulthood—ironic, adrift, disaffected—and there it was. The same dread. The same internalized fear of instant erasure. They spoke in deadpan voices, but what I heard was an echo. A generation moving through optimism with a hairline fracture running beneath it. Nuclear anxiety like a low level hum that never entirely faded.

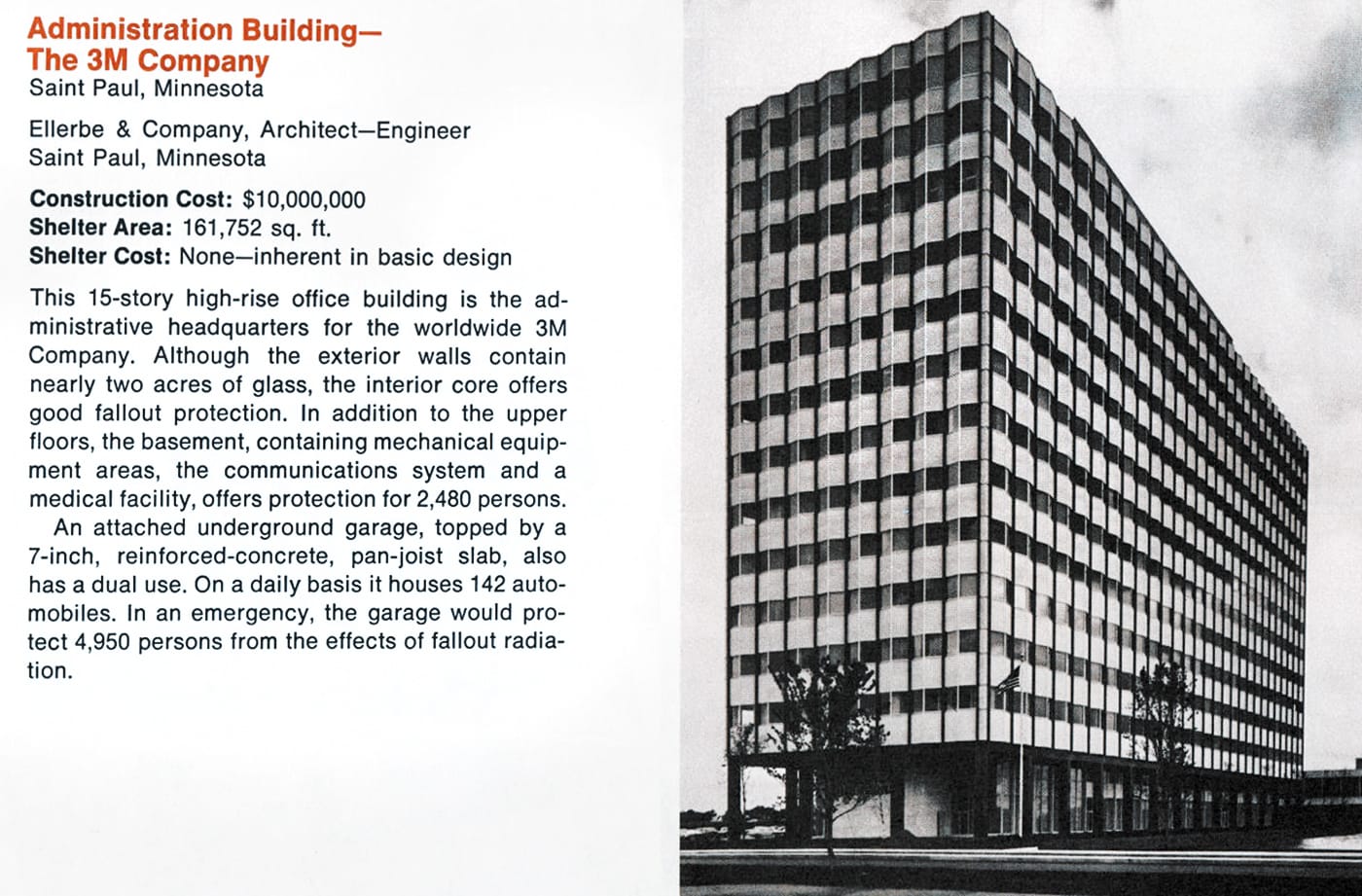

We remember the ’80s for pastel, neon, high gloss. A wonderland of surfaces. But beneath every bright colour, the threat of fallout lingered. It’s no surprise, then, that cities of that era embedded their own quiet redundancies. Not shelters with flags, but voids, reinforcements, unacknowledged designs. The anxiety was ambient. And so was the architecture.

If the 1950s and '60s were defined by imminent threat and explicit shelter infrastructure, by the time I was a kid, many of the signs had faded and the rooms been repurposed. In the decades after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the anxiety of annihilation became a kind of background radiation, but the aftermath remained: hollowed-out government sub-basements, overbuilt stairwells, evacuation maps yellowing in disused corridors.

These were spall from that era, residues of an infrastructure meant to survive a world that had, for an instant, outstripped its own ability to endure. Cities became palimpsests of precaution, inscribed not with the expectation of survival, but with the grim calculus that something could be salvaged or at least endured.

Many of these traces still remain even today, often in plain view, unnoticed until seen anew. Fragments of a future once anticipated, but not (yet) fulfilled.

Sometimes the relics are almost polite. A weathered Fallout Shelter sign bolted to the side of a building, yellow and black fading to rust, a memory of urgency turned obsolete. Once it was a public signal, a promise of shelter, of survivability. Now it hangs without context, ignored by the traffic below.

But the architecture of dread seeped into the foundation long ago. Every extra inch of rebar, every overbuilt junction, a tacit admission that collapse was not only possible, but expected. Even empty places carry this residue, spaces left behind not by destruction, but by design.

At Toronto’s Lawrence Subway Station, there’s a structure known, unofficially, as “the attic.” A strange name, especially underground. It sits above the train platform but below the street—a reinforced cavity, sealed and ventilated, hovering between function and absence.

The depth of the station is deliberate. As the line descends toward York Mills and the low-lying terrain of Hogg’s Hollow, a valley carved by the Don River, Lawrence had to be built deep to accommodate the grade. Maintaining a void above, they say, was cheaper than filling it.

But ventilated cavities are rarely acts of thrift. Lawrence’s attic feels less like an omission and more like a remainder, an emptiness with its own architectural character. Constructed in 1973, it bears the mark of Cold War precaution: hardened, inaccessible, and quietly removed from public space.

A shelter without signage. A contingency without acknowledgment.

In this, it mirrors so much of the atomic legacy embedded in cities. Not plans, but spatial premonitions. Architecture that doesn’t just account for collapse, but rehearses it. And like the fallout shelter signs that still cling to civic buildings, the Lawrence attic is part of a quiet inheritance—a void made ordinary, waiting above our heads, unnoticed and unresolved.

It isn’t alone. Across the urban landscape, voids like this persist: spaces shaped by utility but haunted by dreadful possibility. Underground parking garages with reinforced ceilings. School basements with concrete-blocked windows and century-old water drums. Government buildings with windowless corridors and retrofitted ventilation shafts.

Official explanations abound—codes, budgets, historical layering. But once you begin to notice them, they don’t feel like accidents. They feel like memory, poured into concrete. A latent design language shaped by fear.

Even Toronto’s own transit system once acknowledged this, quietly. In the early 1960s, parts of the subway were retrofitted—or at least designated—as fallout shelters. Maps were distributed. Emergency signage discussed. It was less a promise of protection than a ritual of preparedness, an infrastructural myth meant to reassure more than to rescue.

When the flash comes, some will be sheltered, and others won’t. That hasn't changed.

The suburbs promised safety. A lawn, a fence, a carport. A tricycle left in the grass. But beneath that mid-century stillness, something else took root. In some of those yards—tucked behind hydrangeas, buried beneath poured patios—were the cold, concrete mouths of private fallout shelters. Entrances disguised as garden sheds, ventilation pipes masked as trellises.

Civil Defense campaigns told citizens to duck, cover, and prepare. But the paternalism had limits. In the 1960s, a basic family shelter could cost over $2,000, more than 15% of the average household income. Survival was encouraged, but not provided.

What followed was a paradox. Preparedness was cast as a patriotic duty, but the infrastructure of survival became privatized. Guides recommended building blast doors beside your barbecue. Blueprints circulated in Popular Mechanics. Survival was marketed like a lawn mower or a deep freezer.

The shelter became an accessory to prosperity. A bunker beneath your rambler. You could build one yourself, they said. Just follow the blueprints and bury the fear beneath the patio.

Fast forward, and the form has evolved but not disappeared. The wealthy now commission reinforced compounds with biometric locks, subterranean greenhouses, and wine cellars. New Zealand has become a favoured destination. The aesthetics are sleek, but the impulse unchanged. Fear, outsourced to architecture.

Late-stage capitalism and apocalyptic preparedness are not strange bedfellows. They're the same theology—each devoted to rupture, each worshipping ingenuity over interdependence. In the absence of public faith, contingency becomes a market.

Think of this not as a glitch in the system, but as the system itself. In a world in which threat is ambient, solidarity erodes and salvation is sold by the square foot. The shelter no longer signals paranoia per se. It reflects belief in exclusion. In continuity for some.

If the fallout shelter imagined a single event, today’s infrastructure of anxiety anticipates none. Or rather, too many to count.

We no longer fear annihilation as a moment. We fear accumulation: microplastics, misinformation, autoimmune disorders, extreme weather, and financial collapse. And now, a new spectre: artificial intelligence, draped in the promise of productivity and ease, but trailing an afterimage of displacement and unknowability. The Cold War offered the nightmare of a countdown. Modern life delivers only pressure—vague, persistent, unresolved.

Our dread has dissolved into the everyday. It flickers not in sirens, but in screenlight, alerts cascading across our phones, reminders of a nation always on the edge of something: riots, flood, fire, missing children, chemical spills. The Emergency Alert System no longer signals the end. It just interrupts dinner. A digital knock, cold and toneless. Until the emergency occurs in your midst.

So we adapt. We track our sleep. We monitor the air. We trade privacy for safety, distraction for continuity. Cities are redesigned to be “resilient,” but the word now means yielding, not resisting. It's no longer about bracing against the blast so much as absorbing ongoing threats from all over.

For anyone but the ultra rich, the new shelters are not bunkers. They're conditions: a second home, a way to leave the city, a backup generator. Cold War architecture prepared for the unthinkable. Contemporary design, on the other hand, urges us to think the survivable—constantly. Wellness becomes preparedness. Contingency becomes lifestyle as anxieties proliferate but rarely resolve.

And still, the logic holds. Something might be coming. Or it's already arrived, and we're only now recognizing its shape. The fracture is no longer accompanied by a blinding double flash. It's metastasized, becoming a register distributed across habit, architecture, and thought.

If the nuclear age signed its name in the earth, the present leaves no such signature. Only circuits, networks, rituals, and tides that rise without ceremony.