The shape of dread

Spall 005: From the tetrapod to the lattice

The world is made of shapes. Most serve without asking for attention. They fit our hands, our bodies, our sense of what belongs. Some are tools of comfort, some of harm, but all speak, in their way, our language of form.

And then there are the shapes that don’t. Some feel wrong the moment we see them. Not because they threaten us directly, but because they fail to acknowledge human scale at all. Their geometry seems tuned to some other purpose, something beyond us. And sometimes, these shapes aren’t just unfamiliar; they signal a rupture, a logic beyond our intuitive grasp.

I first recall feeling this particular unease on a trip to the Azores. Driving toward Santa Cruz, the largest town on the small island of Graciosa, I passed a new marina under construction. The harbour was surprisingly blunt and charmless, built for function rather than aesthetics. Its defining feature was a semi-circle break wall curved like a snake made of giant building blocks, familiar in shape, but enlarged in a way that struck me as uncanny.

It took a moment to name the shape’s pull. The form echoed something from childhood, a thing even more basic than the blocky structures before me: a set of jacks, scattered on my bedroom floor, small starbursts snatched up between thumb and finger in a game of lightness and precision. But here was the jack stripped of play, cast in concrete and stacked by the hundreds. The familiar shape made larger, colder, and utilitarian.

The shape in question was the ACCROPODE—or, more specifically, the ACCROPODE II. Both are refinements of an older geometry seen across coastlines the world over: the tetrapod, a sort of master shape that carries a genealogy spanning human hands and the ceaseless confrontation between land and sea.

Even in the calmest hour, the sea’s surface carries immense energy. A single square metre of ocean swell can contain tens of thousands of joules of kinetic force, enough to shatter timber, to crack stone, to wear down steel given enough time. And the sea has nothing but time.

The shore is where that energy lands—quite literally. Relentlessly, the surf pounds the land, and while many waves are small, none arrives alone. The ocean never stops sending them, so, over time, the land crumbles, retreats, and reshapes. The cliff becomes sand, the dune is spread, and the village behind it waits for its turn.

This is why we build. To delay the inevitable. And in doing so, we occasionally abandon the scale of the human altogether, forced by necessity into forms that no longer reflect us. It matters little to the residents of coastal towns that their harbours feature these cold geometries. They’ll take the safety of the barrier, the efficiency of energy distribution. It's a small price to pay for protection.

In 1950, at the Laboratoire Dauphinois d’Hydraulique in Grenoble, France, the tetrapod was born in a wave tank. Engineers at Sogreah were seeking a form that could do what centuries of sea walls, piers, and stone jetties could not. They imagined not a solid barrier, but an interruption, a way to break the wave’s force from within.

The tetrapod was their answer. Four limbs splayed to lock with its neighbours, creating voids that turned wave energy inward, dissipating force through turbulence and drag. The geometry was indifferent to the human eye, belonging to fluid dynamics more than architecture.

Its brilliance lay not only in how it worked, but in how easily it could be made. Poured in concrete, simple to mold, reproducible anywhere. No quarries, no shaping of stone, no long transport of massive blocks. The tetrapod’s simplicity is its genius: uniform units that can be produced at scale, stacked in endless variation, a decidedly modern reef against the sea. Today, there are gentler variants, like the ECOPODE, which is shaped to echo the coastline’s own geology. But they’re used far less often. Irregularity doesn’t scale.

Japan saw this clearly. After the Second World War, in the long project of rebuilding and defending its coastlines from typhoons and tsunamis, the country embraced the tetrapod as a defining feature of its seascape. By the millions they were poured, stacked, heaped along harbours, breakwaters, and fishing villages. The tetrapod became part of the national geometry, as common as shrine gates or power pylons, but stripped of all symbolism.

And from there, they spread. Today, the tetrapod appears on coasts around the world, from the Azores to Hawaii, from Normandy to the Philippines. A global monument to our attempt to hold the sea at bay, replicated wherever the endless needs resisting. The shape’s logic—its scatter, its lock, its resistance—became a template for facing forces at a scale we could not inhabit.

The tetrapod is not the only shape that chills. There's a whole geometry of negation, forms we’ve made for what threatens us. Shapes that don’t fit the hand, the eye, or the body. Shapes that belong, like the tetrapod, to the scale of danger.

Consider the Czech hedgehog, scattered along beaches in the Second World War and notoriously across the "death strip" of the Berlin Wall, an interstice that marked the Cold War in physical geography. Angular iron limbs, set at random-seeming angles to catch and stop tanks, to channel destruction. The hedgehog shares the tetrapod’s logic: no uninterrupted surface, no clear direction, no welcome. A form meant only to resist.

Its name softens the shape’s cruelty. The hedgehog clothes cold iron in a living metaphor, but the bristling spikes of steel are not quills. The name merely helps tame the abstraction, giving language a way to domesticate something monstrous enough that it resists its conventional grasp.

The jack is again the innocent ancestor, a toy whose form far predates the polished metal objects played with today. The game, in one form or another, is ancient: played with knucklebones, pebbles, fragments of whatever was left over. The outline of the shape has long been with us, a geometry that clings, that scatters and holds where it falls.

It’s not hard to imagine that the engineers who designed the tetrapod or hedgehog had seen it on kitchen floors, in schoolyards, in their own childhood palms. And in some unnoticed moment, the logic embedded itself, resurfacing much later in the lab.

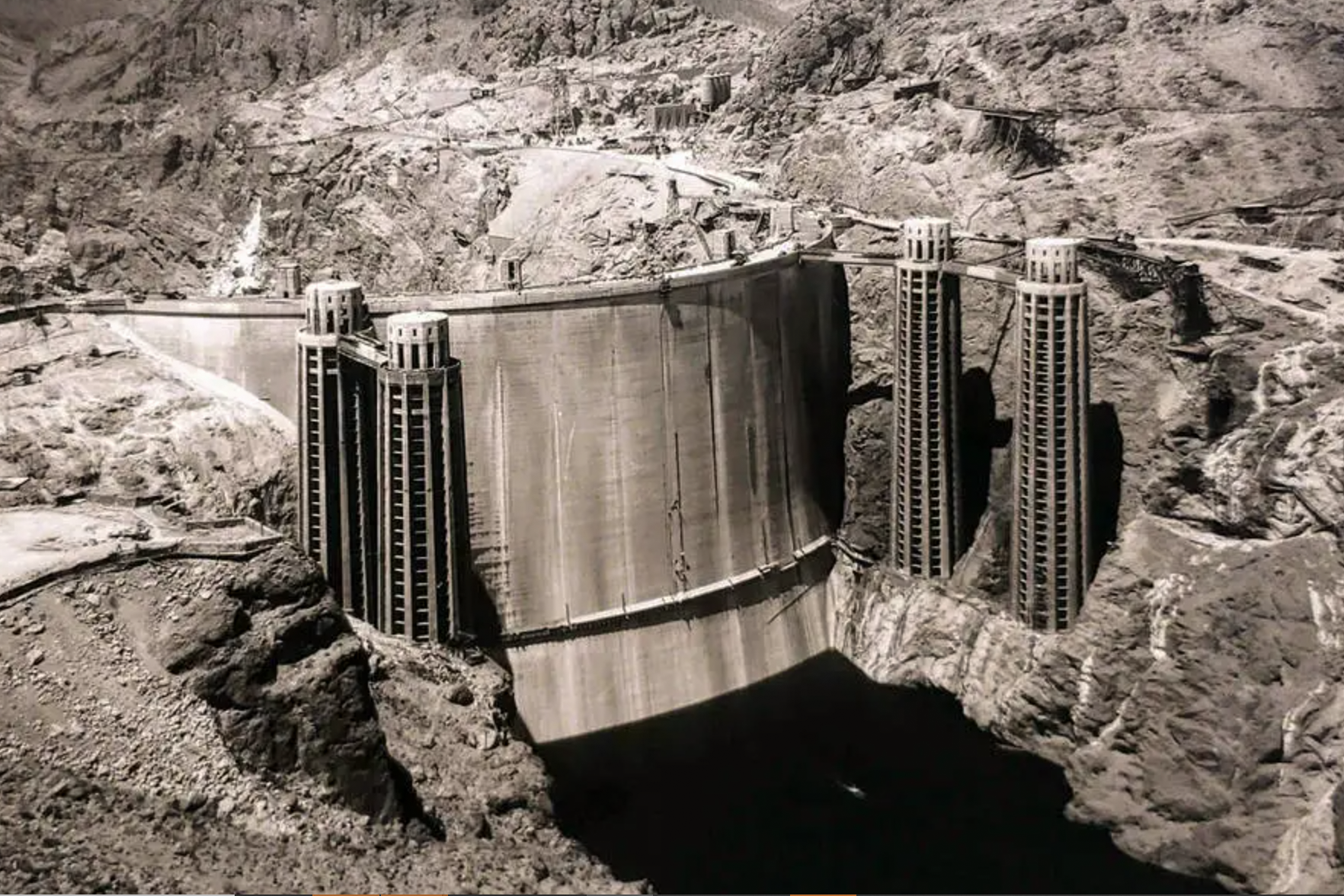

And then there’s the monolith, not the sacred pillar or symbol, but the blank slab of concrete raised by engineers, poured to deflect water, blast, and sometimes, it seems, time itself. A form not for the body to approach, but to turn away. We knew it first in miniature: the low fence in a backyard, the garden wall at the edge of play, the fallen domino. But scaled up, the monolith ceases to acknowledge us. Its face no longer invites leaning, its edge no longer marks a boundary we might cross.

These shapes provoke dread not because they threaten harm directly. They do so because they show what we already suspect: that we design for forces beyond our measure. That we build not to fit ourselves, but to hold at bay forces beyond our control. And that in doing so, we cross a threshold, where shape gives way to structure, and dread migrates from form to logic.

And this is what unsettles us the most. These forms are ours. Their uncanny scale is of our making. The tetrapod, the hedgehog, the monolith are all born of human intent, human calculation. But in serving purposes beyond the human or as tools of violence impossible to reconcile, they abandon us. They show us what our hands can shape when comfort, belonging, and beauty no longer matter.

For a long time, what we made echoed what we knew. A plane looks, if not exactly like a bird, then at least like its technological offspring. A car is not far from the carriage or the horse: four points of contact, a driver in place of a rider. The bicycle extends our stride with almost miraculous efficiency. Even the iPhone, for all its resemblance to a monolith in miniature, fits the hand, wakes at our touch, stays close to the body like a trusted tool. These are shapes that continue the dialogue between our bodies and what we’ve built.

We’ve already seen where that thread begins to fray. The tetrapod and the Czech hedgehog don’t mirror the body, nor do they acknowledge the human at all. They resist forces that endanger shorelines, battlefields, and ideologies. Disconcerting, yes—but still legible. We can name their purpose and trace their shape. But at a certain scale, even form fails. We move from geometries that ignore the body to systems that eclipse the mind. Today, we build not just beyond the scale of the hand, but beyond the reach of thought as we once conceived it.

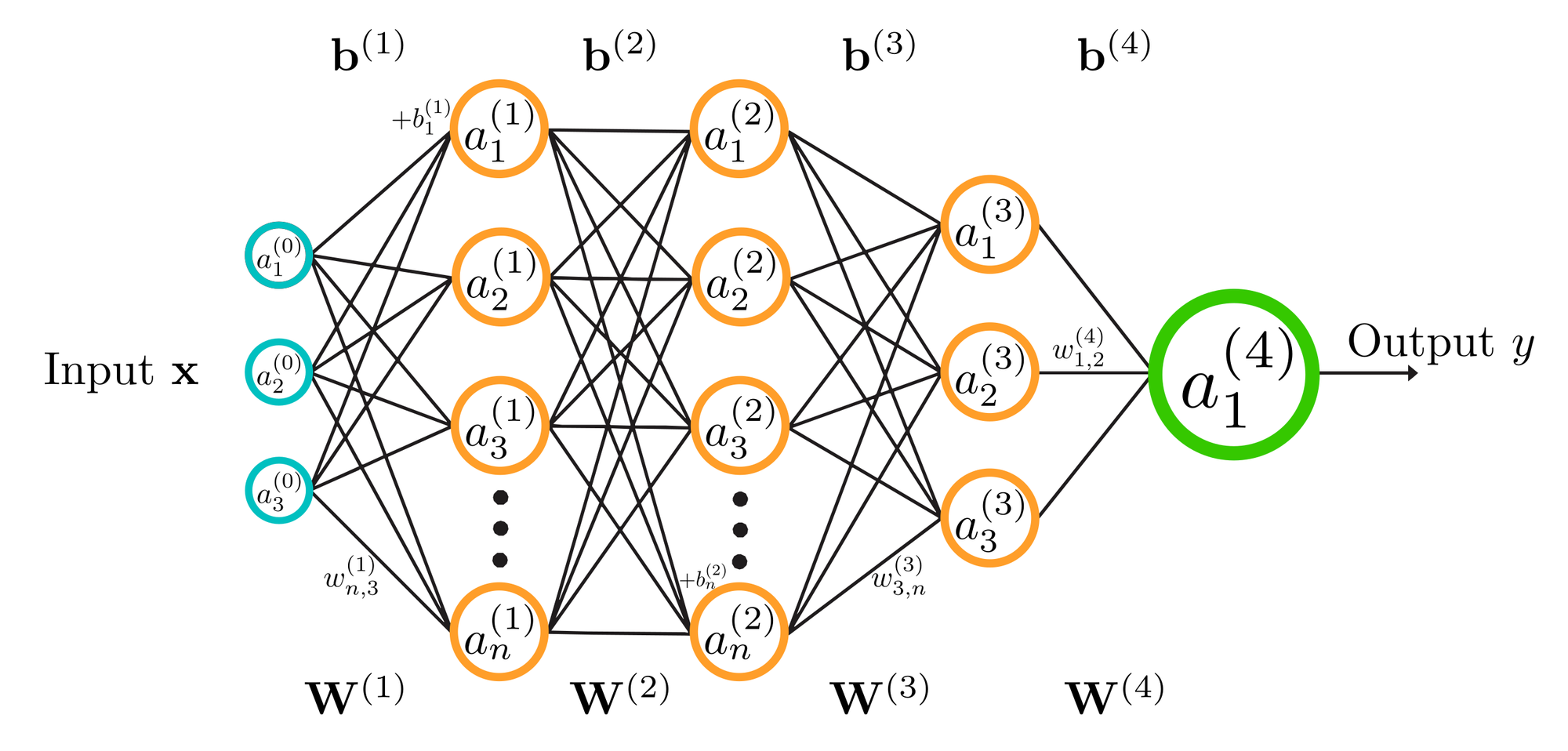

In the 1980s, Geoffrey Hinton and his colleagues at the University of Toronto designed systems modelled on the human brain. They were called neural networks: simple, layered constructions of nodes and weights that mirrored the way we believed neurons and synapses might function. The idea seemed natural, necessary almost. If we could build a machine that learned as we do, perhaps we could understand ourselves better. It was a modest proposition, full of analogy and proximity.

At first, the resemblance held. But scale changes everything. With more data, more layers, and exponentially more computational power, the model’s structure ballooned until its workings no longer corresponded to anything intuitively human. Today’s large language models, built on transformer architectures with trillions of parameters, process language in ways no human could, aggregate traces no one life could contain, and generate associations beyond any person’s conscious grasp.

The resemblance to human thought, Hinton has said, still exists in part. He’s noted that what we call "hallucination" in AI is perhaps better described as confabulation, a pattern-seeking process that’s not alien so much as deeply human. We do this all the time, filling in gaps, inventing coherence, and threading narratives. But here’s the rupture: our confabulations operate within the boundaries of memory, emotion, and biology. The contemporary LLM? It reconstructs the world from a trillion fragments at once.

At some point, the difference ceases to be one of degree and becomes one of kind. The net is no longer a tool in our image, but a structure in its own right, optimized for speed, scale, and statistical power. It's a mesh designed for the flood of information itself. If the early neural net was like a toy, a system we could hold in our mental hands, then what we now face is more like a new shape of knowing altogether.

The logic confounds just as it remains absurdly familiar. These structures don't trace the jack itself, but the entire grammar of the set: the catch, the stack, the cling, repeating in what feels like an endless process. We once scattered these shapes for play. Now we’ve built them into servers and sentences, across our stories and cities. At some point, they may assemble without us.

This new architecture of thought is now made physical via the data centre. These impersonal structures propagate across the landscape, indifferent to the bodily needs of their creators. They are buildings made for machines, spaces for heat, flow, and throughput, a process of continual stacking, interlocking, and multiplication. It's all racks, grids, and cooling towers. An endless hum of power. Vast thinking forms whose contours we shaped but no longer follow.

We learned how to hold back the sea. But along the way, the shapes we built to contain what threatened us became a new kind of danger altogether. The tetrapod could easily outlast us, scattered along quiet shores, its eroded but unmistakable form persisting after its purpose is forgotten. And the lattice we have spun will endure longer still. A geometry of our own making, outliving the hand that shaped it.